May 15, 2014

N.C. Superior Court Judge Howard Manning’s May 5 report on N.C. education is a blunt reminder that North Carolina is failing to educate its children.

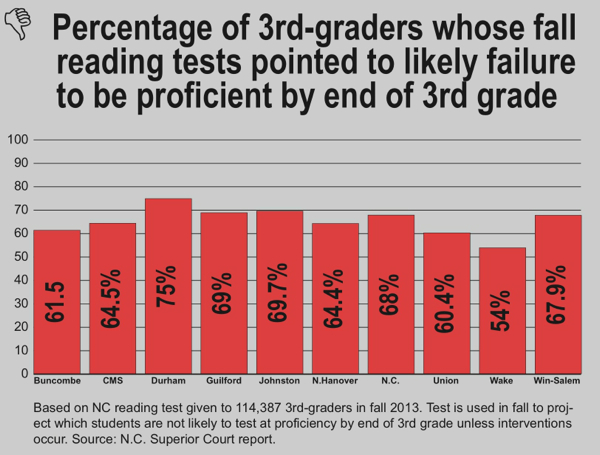

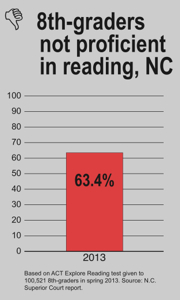

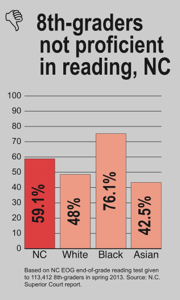

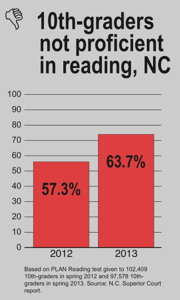

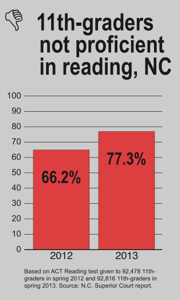

The message can be graphically displayed as in the charts that accompany this article. Manning’s report is full of test data. He argues that in most cases half or more of North Carolina children are not receiving the sound basic education that the N.C. Supreme Court has mandated.

He also argues, as he has for many years, that money alone is not the defining, missing ingredient in achieving a quality education system in North Carolina. Most of the recent report, instead, argues that earlier court efforts have succeeded in giving N.C. principals and teachers the tools they need to know exactly what reading skills are missing, that are keeping each child from reading proficiently. The judge says that software tools tell teachers exactly what needs to be taught. He declares that teachers have refused to alter their teaching routines, and so the children are still not reading well. He faults principals for not insisting that teachers teach the children the skills they need.

He also argues, as he has for many years, that money alone is not the defining, missing ingredient in achieving a quality education system in North Carolina. Most of the recent report, instead, argues that earlier court efforts have succeeded in giving N.C. principals and teachers the tools they need to know exactly what reading skills are missing, that are keeping each child from reading proficiently. The judge says that software tools tell teachers exactly what needs to be taught. He declares that teachers have refused to alter their teaching routines, and so the children are still not reading well. He faults principals for not insisting that teachers teach the children the skills they need.

Perhaps it is all that simple. But Manning has a penchant for viewing education as a linear activity that begins at pre-K and should result in 3rd-graders reading proficiently. But most second-grade classrooms contain children who weren’t in North Carolina for pre-K, who may not have been on this side of the globe in first grade. The judge and the teachers may live in different worlds.

And in his report, Manning seems very focused on dealing only with reading. He’s right to do so in a sense, for reading is the foundational skill required for all other education. But achieving a sound basic education will fall well shy of the mark if North Carolina narrows its ambitions for its children to the skill of reading.

Manning may have wagered that if he’s going to make any headway, he must focus. Fine. But there’s more out there to tackle than K-2 reading scores, and lots of pieces to this puzzle in addition to teachers’ willingness to individualize reading instruction around what students need to learn.

Manning may have wagered that if he’s going to make any headway, he must focus. Fine. But there’s more out there to tackle than K-2 reading scores, and lots of pieces to this puzzle in addition to teachers’ willingness to individualize reading instruction around what students need to learn.

It was an achievement to get the courts to rule that the constitutional guarantee of a sound basic education should apply to every child. And it was another achievement to define what that meant, both in terms of the skills every student should acquire, and the teaching, leadership and instructional resources that every child should have available, no matter where they are assigned.

But those are yesterday’s achievements. And yesterday never brought the political consensus that would make all of that happen for all children across North Carolina. Manning quotes the N.C. Supreme Court opinion in Leandro II:

“Assuring that our children are afforded the chance to become contributing, constructive members of society is paramount Whether the State meets this challenge remains to be determined.”

That opinion was from 2002 and, arguably, little has changed in the intervening 12 years. So how do we get closer to the goal?

Manning wants to wait for another data set of test scores. And perhaps on seeing them he’ll want to wait for another set of scores, perhaps from the original plaintiff counties, rural areas that have not figured much in Manning’s courtroom inquiries lately. And after those scores are in? Manning is a very nice man, but it might be easy for impatient schoolchildren to conclude that they’ll be grandparents before any substantive changes arrive in N.C. classrooms.

That conclusion is made even more plausible by the litany of shame, provided by plaintiffs in a court filing, that details all the programs that N.C. legislatures put in place to meet the Leandro challenge, only to see subsequent legislatures gut, defund, underfund, ignore or legislate them out of existence. The list is long:

That conclusion is made even more plausible by the litany of shame, provided by plaintiffs in a court filing, that details all the programs that N.C. legislatures put in place to meet the Leandro challenge, only to see subsequent legislatures gut, defund, underfund, ignore or legislate them out of existence. The list is long:

– The legislature eliminated a number of high school end-of-course testing programs on which the court depended for information about student achievement. They ordered use of the ACT, a nationally normed test, so students taught an N.C. curriculum face a test designed around a different curriculum.

– The State Board of Education in 2009 adopted mandatory K-2 assessment standards for asessing academic achievement, but included no enforcement provisions.

– When the Supreme Court ruled that the basic framework of N.C. education was sound, N.C. teacher salaries ranked 27th in the nation. Now they’re 46th and many of the competent teachers the court expected every child to have access to are working in other states or in banks or retail shops or wherever.

– During the recession, the legislature cut many of the state’s programs that led the court to declare the state’s education system adequate. Examples: Additional assistant principals, teacher assistants, textbooks, staff development and assistance for children with limited English,

– And in a period when the number of N.C. children receiving lunch assistance rose from 38.9% to 48.5%, the legislature cut funding for programs giving schools more help meeting these same children’s needs, including the Disadvantaged Student Supplemental Fund, slots in the state’s pre-K program, and of course by packing classrooms as student-teacher ratios rose with the elimination of 5,200 teacher positions.

– In the current budget year, a long time after the recession ended, the legislature was still slicing millions from instructional supplies funds, and eliminating 3,850 teacher assistant positions.

– In the current budget year, a long time after the recession ended, the legislature was still slicing millions from instructional supplies funds, and eliminating 3,850 teacher assistant positions.

The legislature has returned to its short session as this is being written. Leaders have nominally embraced a pay plan for teachers and state workers prepared by Gov. Pat McCrory. What will emerge from their hothouse session is anyone’s guess. But what will not emerge is fairly clear.

The state is so far behind in teacher pay that the wave of teacher losses will barely abate. The Supreme Court has cleared the way for siphoning public funds to mostly religious schools through the so-called “opportunity” scholarships approved earlier but tied up from the beginning in litigation. None of this bodes well for North Carolina, as the Manning court puts it, becoming “Leandro-compliant” any generation soon. Something must change on the ground.

Gov. McCrory could have changed things on the ground. But Art Pope is firmly in control, and the state’s wealthiest individuals and corporate entities will not be obliged to pay more toward creating the better-educated workers on which their own economic future depends. Think about that.

Judge Manning could change things on the ground. Send a bunch of elected officials to jail for contempt of court? Sadly, it’s clear that the judge will never send his former legislative colleagues to jail. He has had so many opportunities to order them to commit resources to the work that must be done to abide by the N.C. Supreme Court’s earlier rulings in the Leandro case that educators have all but given up hope that the court will effectively intervene.

Judge Manning could change things on the ground. Send a bunch of elected officials to jail for contempt of court? Sadly, it’s clear that the judge will never send his former legislative colleagues to jail. He has had so many opportunities to order them to commit resources to the work that must be done to abide by the N.C. Supreme Court’s earlier rulings in the Leandro case that educators have all but given up hope that the court will effectively intervene.

That leaves change to those who have already benefitted from education improvements to reach back and advocate for those not yet served. That was the message this week from the White House, which released a proclamation on the occasion of Saturday’s 60th anniversary of the Brown vs. Board of Education ruling:

“On the 60th Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education,” President Obama said, “let us heed the words of Justice Thurgood Marshall, who so ably argued the case against segregation, ‘None of us got where we are solely by pulling ourselves up by our bootstraps. We got here because somebody…bent down and helped us pick up our boots.’ Let us march together, meet our obligations to one another, and remember that progress has never come easily – but even in the face of impossible odds, those who love their country can change it.”

– Steve Johnston